Preservation and restoration at Raheen-a-cluig church

The structures at Raheen-a-cluig, as they stand today, are partly the result of preservation and restoration efforts, undertaken when the site was taken into the care of the State in 1926.

Files from the Office of Public Works from the 1920s and 1930s give an interesting insight into these works, the risk of damage to the site and the philosophy of the emerging National Monuments Service.

Background

In June 1925, the Bray Town Clerk, Seán MacCathmhaoill, wrote on behalf of the Urban District Council (UDC) to the Commissioners of Public Works, asking what formalities were needed to get the Commissioners to take over the care of the ruins of Raheen-a-cluig church. These were located in what he called the ‘new park’ on Bray Head, i.e. land that had been recently granted to the Council by a Mr. David Frame.

The Commissioners informed the Town Clerk that the Council could pass a motion to offer to transfer their interest in the church site to the Commissioners. The site would then be inspected by the ‘Inspector of Ancient Monuments’, Harold Leask (Fig. 1), and a decision made by the Commissioners. The UDC swiftly passed the appropriate resolutions and Mr. Leask inspected the site in August 1925. (Harold Leask would later go on to become a leading figure in the areas of conservation and Irish medieval architecture but was then at an early stage of his career, see further reading below.)

What was there in 1925 and what was added?

What was there in 1925? The earliest surviving photograph of Raheen-a-cluig was published around 1875 (Fig. 2). It is not known who took the photograph, but it clearly shows the church ruins, with Victorian Bray in the background. The ruins are in two parts. The western end, on the left in the photo, has a fairly intact end wall with parts of the side walls projecting from it, while the eastern end, on the right, consists of an end wall but with a sharply overhanging gable on one side and little in the way of side walls.

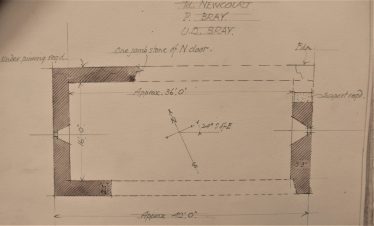

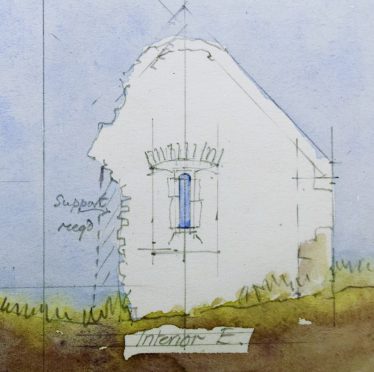

Leask found these remains essentially unchanged in 1925. He made a plan drawing (Fig. 3) and also two elevations of the western and eastern ends, as seen from inside (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5), showing the structures broadly as they appear in the 1875 photograph. He also took some photographs of his own. (An enhanced version of one of his photographs is shown in Fig. 6.) Leask noted that the ‘standing portions of the walls are in fair repair’ and they ‘will not require any very extensive work’. He noted, however, that some interventions were required, in particular, an ‘underpinning’ at the north-west gable and, obvious from the photographs, ‘a support to (the) overhanging part of the east gable’.

He refers to the ruins as being those of one of ‘these small rather featureless churches which are fairly common’. Despite that, he goes on to say that it ‘is, however, worthy of preservation, and in my opinion there is a distinct advantage in taking visible charge and care of even so simple a building in such a frequented place, in that numbers of people may become aware, not only that such things are worthy of preservation, but that they are being preserved’ (emphasis added). He then refers to recent letters in the public press that ‘appear to have been written in ignorance of what has been done and is being done in the preservation of ancient monuments’.

The Commissioners took over the site in early 1926 and arranged conservation works. These included removing all the ivy and other growth, putting in a support for the overhanging gable, underpinning the north wall, searching for and ‘bringing up’ the foundations of the remainder of the north wall and a number of other items. The estimated cost was £35 which, adjusting for general price inflation, is the equivalent of about €2,360 today. (Fig. 7 shows the eastern end wall, as it appears today from inside, as well as members of the Medieval Bray Project.)

‘Nuisance’ at Raheen-a-cluig

During the works, the Council wanted the interior fenced off, as it was being used for picnics and ‘nuisance is also committed’, according to the Town Clerk. The Commissioners were firmly against this, however, as they considered that even an elaborate fence was unlikely to exclude determined members of the public and it would block access to the monument for those genuinely interested in it. The view was that cleaning up the ruins and fixing a notice to them would be sufficient.

The notice that was put up was a forerunner of the ‘Fógra’ notice now on many national monuments. The exact wording was provided by Leask to his superior, Commissioner Le Fanu. (Thomas Le Fanu was a Commissioner of Public Works in 1926 and was, at various times, the Vice-President of the Royal Irish Academy and President of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland.) The notice referred to the Ancient Monuments Protection Act (1882) and the possibility of ‘severe punishment’ for interfering with the ruins.

It was conceded by Leask to Le Fanu that only time would tell whether this approach would be effective. It is clear from a further entry in the file for February 1935, that this was not entirely so. The original notice had been damaged by stone throwing and had to be removed. The Commissioners were not deflected from their approach, however, and they replaced the notice with another one fixed higher up on the church wall in a place ‘less obvious to stone throwers but still reasonably visible to visitors’.

Conclusion

While preservation and restoration might not be carried out in exactly the same way today, it is clear that some of the structural supports provided in 1926 were needed, simply to stabilise the remaining structure and to allow the public safe access to it. The emerging National Monuments Service was clearly keen for the public to access it and to appreciate the ruins and the importance of preserving such structures. While they did not install any detailed description of the site or surrounding features, little was known about it at that time. Subsequent efforts, in particular, excavations by the Medieval Bray Project, have uncovered more about the site’s past.

Further Reading – Carey, A. Harold G. Leask: Aspects of His Work as Inspector of National Monuments, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 133 (2003), pp. 24-35.

This post is based on the publicly accessible archives of the National Monuments Service.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page